Important features of Economy of middle and upper ganga valley during the period from 6th century BCE to the early 4th century BCE.

After a millennium or so there was again evidence of

urbanisation in the areas around the ganga valley after the Harappan

civilization. It is generally supposed to have begun around 600 B.C coinciding

with the beginning of early historic period in Gangetic valley.[1]

In terms of ecology and archaeology there appears to have been a distinction

between the western Ganga plain and the middle ganga plain in 2nd

millennium B.C. with similarities appearing only with middle of 1st

century B.C. with the use of distinctive Northern Black Polished Ware.[2]

It is seen to be a period of emergence of fortified settlement like Champak, Kombi,

Ujjain, introduction of Northern Black Polished Ware, iron based agricultural

economy, long distance trade, stable political structure, stratified society ,

emergence of bureaucracy etc. raising the point of emergence of initial stages

of state formation.

Considering Pearson definition of Economy as a social

process of interaction between man and his environment in the course of which goods

and services change form, are moved about and change hands[3]

where its institutional form are resultants of several independent levels of

human existence, ecological, technological, social and cultural there is

clearly economic activity described in Buddhist literature for the period

between 6th century BCE to 4th century BCE however, we

lack statistical data to prove these interconnections. Buddhist sources

suggests a prosperous economy in a state of expansion.[4]

Greg Bailey and Ian Rabbet argue that the Vedic literature where economic

conditions are defined with much narrower base are strikingly contrasted with

those of Pali text which are immediately struck by the difference in landscape

in which economic conditions are projected. Most strikingly the presence of

large cities flourishing because they are present at junctions of trading

routes.

While coins may have been present during the period, they

are punch marked or uninscribed cast variety and they themselves are dated

through archaeological record rather then providing the chronology of the

period. The dating’s of this period based on ceramic assemblage which was

mostly highlighted for Ganga valley reasons with the works of Krishna Deva and

Wheeler, the focus was on the Northern Black Polished Ware. However this dating

remains illusionary and there are lot of limitations while averaging its date

of appearance, Erdosy points out the early NBP phase to BC 550-400 approximately,

middle phase to BC 400-250 and late phase to BC 250-100 and based on this

appearance of coins to the subcontinent is dated only to end of 400 BC by him.[5]

The dating of the PGW layers containing iron objects roughly coincides with

that of the later Vedic texts. Although some enthusiasts would like to push

back the date of both the PGW and iron levels on the basis of a single

carbon-14 dating from Atranjikhera, the overall picture comprising the

diffusion of the PGW with iron covers period of less than five centuries from

c. 1000 B.C. to about 500 B.C.[6]

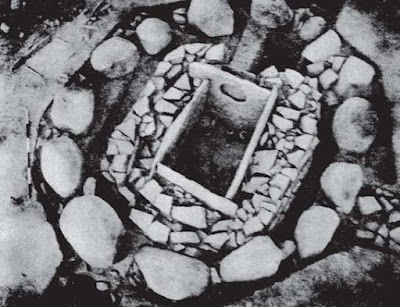

The modern Allahabad with its largest site Kausambi is seen

to be the heartland of early NBP phase and was surrounded by a monumental earthen

rampart. Period two shows large increase in its size with population growth

indicating rapid political and economic centralisation according to Erdosy. It

is argued on the basis of surface finds, settlement location and literary

evidence that settlements were basically divided into 3 zones. The villages

might be dominated by people practising agriculture and herding. Above them

were minor centres revealing traces of the manufacture of ceramics and lithic

blades, as well as iron smelting to which marketing, policing and tax

collecting function may also be attributed.[7]

Next were the towns providing a full complement of manufacturing activity.

A comparative study of the early and late Vedic texts

suggests a gradual change from pastoralism as the predominant economy to

agriculture superseding pastoralism, although the latter never totally declined

in the western Ganga Plain.[8]

There is great variability in the economic pattern area wise, for example

region around Mathura are considered to be pastoral but it is very limited in

the middle Ganga Plain. Romila Thappar takes the example of Rajasuya sacrifice

to prove this argument where it appears that offering based on grains are more

frequent then cattle sacrifices. Several PGW sites have 3-4-metre-thick

deposits which suggest continuous habitation based on assured and continuous

means of subsistence. These habitations clearly show that agriculture had

become the main occupation of the people.[9]

The later Vedic texts show that people produced not only

barley, which is mentioned in the Rig Veda, but also wheat, several kinds of

pulses and, above all, rice. They also produced mudga which takes 6-8 weeks to

ripen, and they grew kulmasa or mad which was considered to be the food of the

poor in times of famine in the Kuru land.[10]

Although the wooden ploughshare was the main instrument of production, the

later Vedic people had a better knowledge of

seasons, used manure, and practised irrigation.[11]The

evidence of iron since beginning of 1st millennium B.C. from the

upper Gangetic valley has led to the argument of use of iron for clearing the

forest to do large scale cultivation. This theme came into focus when Kosambi

argued that the large-scale clearing of the forest in Gangetic valley could not

have been undertaken without the use of iron. But so far very few iron tools

belonging to the first half of the first millennium have been discovered, which

suggests that at this stage iron did not contribute to handicrafts and

agriculture. The evidence of an iron ploughshare does only come from around 500

century B.C from Eta district in U.P. However,

in 1ST half of the first millennium iron may have been used for

clearance, for making wheels and the body of carts and chariots, and in the

construction of houses because nails have been recovered from several PGW

sites.[12]

However, the early Indian literature points to association

of iron with agriculture in Gangetic valley by about 700 B.C. Buddhist text

also show it. The Kasibharadvaja Sutta of the Sutta Nipata gives the analogy of

a ploughshare which having become heated during the day, hisses and smokes when

plunged into water. The analogy is repeated in Mahavagga.[13]

Buddhist literature also points in many other ways in which agriculture was

important during the 600 B.C. Many Vinaya rule are related to crops. For

example, there was an institution of vassa-vasa for rain retreat of monks as

people complained of crop damage by travelling bhikkhus. If not iron say if

there was use of wooden ploughshare to cultivate but this also becomes

problematic as for the type of the hard clayey soil we generally have in the

alluvial tracts of the middle Gangetic basin such shares are not effective. In

parts of Patna district, the soil locally known as the kewal is so hard that

once it dries up even iron shares are sometimes found inadequate to break it. So,

use of iron thus becomes very important for cultivation to have existent in the

region on large scale. R.S Sharma argue that the reason for no ploughshare to

has been discovered might be due to ecological reasons. The acid, humid, warm

alluvial soil of eastern UP and Bihar has proved to be highly corrosive. It is

good for rice production but bad for the preservation of iron artefacts.[14]

Uma Chakrabarti points out the extension of agriculture in

mid Ganga plains as primarily a rice phenomenon as the area due to perennial

supply of water suited it. She and R.S Sharma argue that the method of paddy

transplantation was probably learnt during this period.[15]

Moreover practice of plantation was well developed during this time as we also

have evidence of banana plantation to be started during the period. Also, the

Jaina and Buddhist canonical text suggests detailed process of cultivation to

have been practiced as process of breaking of soil before making it wet for

plantation and the maintenance of proper dykes and water channels to have been

there.

One way in which the economy of period can be looked upon is

by examining the changing meanings of the word Gahapati used during the period.

The term meaning Grihapati in Sanskrit appears in Rigveda and is used for

householder and master of house but as Uma Chakravarti argues this definition

is insufficient and the word has broader meanings. Gahapati is seen associated

with property owner and a major tax payer in the Buddhist text. The

Samannaphala Sutta of the Digha Nikaya states that gahapati is a free man, one

who cultivates his land, one who pays taxes, and thus increases King’s wealth.[16]

However, there are other expressions too in association to which the word

appears like there is use of expression like setthi-gahapati in the texts but as

pointed out by Uma Chakrabarti the word setthi, setthi-gahapati and gahapati

are never used interchangeably in the text suggesting that they might have

represented different conceptual categories in Buddhist society. Further, it is

seen that set this and setthi-gahapatis are most frequently located in the big

urban centres of Varanasi and Rajagaha suggesting they had great wealth.

The gahapati is also seen with those who paid the regular

taxes. The evidence of taxes such as bali and bhaga which in Vedic societies

were just offerings took a defined shape during this period and it is seen that

it was desired. The bhaga generally computed at one-sixth of the produce; they are

collected by king’s officers and are collected at a contracted time.[17]The

evidence of taxes imply that surplus has to be conserved as it has to be paid

to king and has also to be kept for personal use and this imply accumulation of

wealth as a concept developing during the period remarking Gahapati to be able

to do it in large number. Romila Thappar argues that probably from this class

emerged the full time, profession of traders and merchants.

As far as trade is concerned, the Buddhist literature is

full of references to trading caravans, guilds of merchants, market towns and

roads along which trading caravans moved[18]

signifying trade was important part of the economy. There are not only references

to intra-regional but also inter-regional trading system. There were trade

routes linking middle Ganga to its rising cities as well as to far of places

like Afghanistan and Iran. Vanijja was the general term used for commercial or

trading activities. In an excerpt from Majjhima Nikaya, Buddha is seen

favouring the trading(vanijja) over agriculture where he claims that trading

involves far less duties, administration and problems and yet a successful

venture brings in great profit.[19]The

use of coinage is associated with long distance trade. As the quantity of coins

discovered is much in numbers it indicates flourishing trade also there was

invention of punch marked coins elaborating the argument further.

Archaeological evidence for urbanisation also termed as the

period of 2nd urbanisation comes from around mid-first millennium

B.C. from various sites of Ganga plain. There are about sixteen great states

(16 Mahajanpada) which is shown by the Pali texts. However, in the absence of

horizontal excavations it is difficult to reconstruct the process of evolution

towards urbanism.[20]

Romila Thappar shows that there can be numerous ways in which urbanisation can

be defined. It can be defined on the basis of production of agricultural

surplus when the city which is defined has very people who can produce their

own food. If the city is essentially an administrative centre it requires a

political context to support such administration. Cities can also grow out of

ceremonial centres where a religious nucleus provides the reason for the

concentration of people.[21]Also

a city can also develop as a place of exchange.

Recently, an effort is made to study the size of settlement

and by noticing the changes in size determine how an urban centre has even

developed. Erdosy has looked upon this aspect in the context of Allahabad

district Kausambi which is known from literary sources to be capital of Vatsa

Janapada. He argues that this settlement grew by about 50 hectares and was

surrounded by a monumental earthen rampart by 400 B.C and there was also a

population growth of at 68 per cent per annum during this period which was

absorbed through agglomeration as this massive increased population was

adjusted beneath only 21 sites. Thus, witnessing rapid political and economic centralization.[22]

Krishna Mohan Shrimali, referencing his arguments on the

basis of Pali literature argues that rise and expansion of territorial states

during the three centuries beginning with c.500 BCE was a product of the growth

of agriculture. He argues that since early states grew largely in the riverine

plains which is the most hospitable area for agriculture, probably this was the

basis of developments of states according to him. According to him areas especially

near to Gangetic valley which were rich in agriculture acted as a nuclear area

around which settlements flourished. He says that the urban economy was more

mercantile than agrarian and the rural was more agrarian than urban. According

to him even the villages of this period were important from industrial point of

view as there is presence of possibly five craftsmen( carpenter, ironsmith,

potter, barber, washerman) in the villages.

Romila Thapar argues that the introduction of coined

metallic money marked a major change in urban life. As according to her the coined

money extends the geographical reach of trade and brings distant centres into

contact leading to exchange of ideas and script and in fact, according to her

evolution of Brahmi and Kharosthi was due to this. She also points that urban

needs led to emergence of a large number of new professions as with greater

demand of products there must be concentration of artisans in the town.[23]

Probably this congregation led to identification of these occupational with

certain castes in Indian society.

Also, there is evidence of emergence of number of market

towns along the trade routes forming linking points. Joshi has pointed to a

verse in the Sutta Nipata which enumerates a number of market towns on the

trade route connecting Assaka with Magadha. Joshi has argued that urbanization

began with the adoption of monetary exchange and this was part of an economic

phenomenon which transformed the barter-based economy of rural area and linked

it with the exchange structure of those days.[24]It

is argued that this urban growth led to the emergence of factors of political

power as only under a consolidated power structure socio-economic factor could

be effectively integrated.

Birendra Nath Prasad has pointed to the differential degrees

of Urbanization an area can have as different regions evolves with the

interplay of different factors in which a certain factor or a set of factors

can be more central to the whole process in shaping the trajectories of

urbanisation in the region. He looks upon urbanisation in the specific context

of Vaishali. The study of Vaishali becomes important as it was an important

political and urban centre in early historic India and its evolving nature of

urbanisation can put glimpses on the broader debate concerning the early

historic urbanization of the Indian subcontinent through a comparative analysis

of their respective features.[25]He

argues that the commonality in morphology, character and functions between the

early historic urban centres in Ganga valley point that they did not existed in

isolation. He has shown that developments in Vaishali began with the foundation

of Vajjian capital since 6th century BCE onwards but it did not

reach a concrete form in the shape of fortification until the Sunga period.[26]Since

it is assumed that Vaisali stood at the top of settlement hierarchy as far as

Videha region is concerned as per the Erdosy’s measurement shows that other

urban centres during the period were also in developing state and were not

fully urbanised during the 6th century to 4th century

BCE.

In spite of the fact that urbanisation and early state

formation is well documented in the texts, the archaeological findings are

still not sufficient to prove this argument. There is still an ongoing debate

of whether the use of iron was a prime mover in the urbanisation process.

Materialist historians inspired by V. Gordon Childe argue that the use of iron led

to technological revolution which led to the clearance of forests and

cultivation of fertile soils of Ganga basin, and the surplus production from

which led the state to prosper. This view is challenged by archaeologists like

Chakrabarti and Ghosh who argued that even major inventions had little impact

until changes in the socio-political sphere prompted their full utilization.[27]

D.K Chakrabarti even points to difficulty in tracing the

beginning of early historic urban growth to 6th century B.C. as the

NBP found in the area go back to c. 700 B.C but the antiquity of early historic

writing does not go beyond to Mauryan period. But there is possibility to be

writing to be present but might have been written on infallible material as

without its Vedas could not have been formulated in later times. Archaeologists

like A. Ghosh and Niharanjan Ray also do not agree to the point of 6th

century B.C to be of urban growth as according to Ray excavations at the sites

which are mentioned in Buddhist text has not revealed, by and large any

impressive structural remains during that period.[28]

D.K Chakrabarti in his article Iron and Urbanisation argues

that since use of copper implements was marginal during the period and there is

evidence of iron to have been used in the lay out of new settlements, clearly

the period was sustained by iron technology but he puts the question of extent

of use of iron in the urban transformation that occurred. He argues that this

extent of change depends on the scale of change a society underwent. With the

example of use of furnaces, he argues that it is the scale of operation to which

a society uses a technology does matter and not just the invention of the

technology. Thus, he argues that use of iron may not have been central to

urbanisation to the period of 6th century B.C but its invention must

have influenced the society which must have underwent changes slowly to exploit

iron in later phases.

Though there is lack of archaeological data for the period

to form some concrete notion about the economy the references associated with

the existent text can not be denied. Anyways, archaeology has its own

limitations too therefore even this field is not sufficient to provide concrete

arguments therefore it becomes necessary to rely on literary evidences and as

seen above literary evidence do point to evidence of a period which was remarkable

from its earlier period in the expansion of agricultural, trading and

settlement practices clearly showing flourishment of economic activity and

coming of urban centres. However, keeping in mind the dearth of evidences we

cannot define the exact extant to what the economic prosperity was present in

the period to call it as period of 2nd urbanisation in Indian

context but there was definitely great flourishment of economic activity during

the period.

REFERENCE: 1) Chakrabarti, D.K. 1984-85. ‘Iron and

urbanisation: An Examination of the Indian Context’. Puratatatva.Vol.15.

pp.68-74.

2) Thapar, Romila. 1995. The First Millennium BC in Northern

India in Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History, pp.80-141. Bombay:

Popular Prakashan.

3) Chakravarti, Uma. 1987. The Social Dimension of Early

Buddhism. Cambridge University Press.

4) Prasad Birendra Nath. 2014. ‘Urbanisation at Early

Historic Vaishali,c. 600 BCE-400 CE’. In D.N Jha (ed.). The Complex Heritage

of Early India: Essays in Memory of R.S. Sharma pp.213-242. Delhi Manohar

Publishers and Distributors.

5) Erdosy, G.1995. ‘City States in North India and Pakistan

at the time of the Buddha. In F.R Allchin (ed.). The Archaeology of Early

Historic South Asia. Cambridge University Press.

6) Shrimali, K.M.2014. ‘Pali Literature and Urbanism’. In

D.N Jha (ed.). The Complex Heritage of Early India: Essays in Memory of R.S.

Sharma pp.213-242. Delhi Manohar Publishers and Distributors.

7) Sharma Ram Sharan.1983. Material Culture

and Social Formation in Ancient India. Delhi Macmillan

8) Bailey, Greg& Mabbett, Ian (eds). 2003. The

Sociology of Early Buddhism. Cambridge University Press

[2] Thapar, Romila. 1995. The First Millennium BC in Northern

India in Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History, pp.80-141. Bombay:

Popular Prakashan. Pg-90

[3] Bailey, Greg&

Mabbett, Ian (eds). 2003. The Sociology of Early Buddhism. Cambridge University

Press.Pg-56

[4] Ibid. Pg-57

[5] Erdosy, G.1995. ‘City States in North India and Pakistan at

the time of the Buddha. In F.R Allchin (ed.). The Archaeology of Early

Historic South Asia. Cambridge University Press.

[6]

Sharma Ram Sharan.1983. Material Culture and Social Formation in Ancient

India. Delhi Macmillan. pg 57-58

[7] Erdosy, G.1995. ‘City States in North India and Pakistan at

the time of the Buddha. In F.R Allchin (ed.). The Archaeology of Early

Historic South Asia. Cambridge University Press

[8] Thapar, Romila. 1995. The First Millennium BC

in Northern India in Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History,

pp.80-141. Bombay: Popular Prakashan. Pg- 97

[9] Sharma

Ram Sharan.1983. Material Culture and Social Formation in Ancient India.

Delhi Macmillan PG- 70

[10]

Ibid. pg- 71

[11]

Ibid. pg -70

[12]

Ibid. pg-72

[13]

Chakravarti, Uma. 1987. The Social Dimension of Early Buddhism.

Cambridge University Press. Pg-18

[14] Sharma

Ram Sharan.1983. Material Culture and Social Formation in Ancient India.

Delhi Macmillan pg- 94

[15] Chakravarti,

Uma. 1987. The Social Dimension of Early Buddhism. Cambridge University

Press. pg-19

[16]

Ibid. pg-70

[17]Thapar,

Romila. 1995. The First Millennium BC in Northern India in Recent

Perspectives of Early Indian History, pp.80-141. Bombay: Popular Prakashan.

Pg- 114

[18] Bailey,

Greg& Mabbett, Ian (eds). 2003. The Sociology of Early Buddhism.

Cambridge University Press. Pg-61

[19] Shrimali, K.M.2014. ‘Pali Literature and Urbanism’. In D.N

Jha (ed.). The Complex Heritage of Early India: Essays in Memory of R.S.

Sharma pp.213-242. Delhi Manohar Publishers and Distributors.pg- 265

[20] Thapar,

Romila. 1995. The First Millennium BC in Northern India in Recent

Perspectives of Early Indian History, pp.80-141. Bombay: Popular Prakashan.

Pg-111

[21] Ibid.

pg- 112

[22] Erdosy, G.1995. ‘City

States in North India and Pakistan at the time of the Buddha. In F.R Allchin

(ed.). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia. Cambridge

University Press. pg-107

[23]Thapar, Romila. 1995. The First Millennium BC in Northern

India in Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History, pp.80-141. Bombay:

Popular Prakashan. Pg-116

[24] Chakravarti, Uma. 1987. The Social Dimension of Early

Buddhism. Cambridge University Press. Pg-21

[25]Prasad Birendra Nath. 2014. ‘Urbanisation at Early Historic

Vaishali,c. 600 BCE-400 CE’. In D.N Jha (ed.). The Complex Heritage of Early India:

Essays in Memory of R.S. Sharma pp.213-242. Delhi Manohar Publishers and

Distributors. Pg-215

[26] Ibid.Pg-227

[27] Erdosy,

G.1995. ‘City States in North India and Pakistan at the time of the Buddha. In

F.R Allchin (ed.). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia.

Cambridge University Press. Pg- 119

Best eCOGRA Sportsbook Review & Welcome Bonus 2021 - CA

ReplyDeleteLooking for 출장안마 an eCOGRA herzamanindir.com/ Sportsbook Bonus? At this eCOGRA Sportsbook review, we're talking about 바카라 사이트 a https://deccasino.com/review/merit-casino/ variety of ECCOGRA sportsbook 바카라 promotions.