Hinduism expansion in India: Annihilation or assimilation?

Hinduism

considered among one of the largest Religion in world has been rethought for

decades now and scholars has begun questioning its origin and nature. Due to

its broad and panoptic nature it subsumes among it a lot many practices, custom

and tradition. Moreover, when many scholars argue that Hinduism is just a name

given to myriad of accumulated cultures is begun to be seen as a religion only

from 19th century. Hence, it has become very important today to know

about its true character. Appropriation and Assimilation runs simultaneously in

the process of making any entity. In case, of Hinduism this must have been the

case however, it becomes important what was on greater side also, the tribal

nature of Hinduism we see today has it been incorporated into it? Or is it the

opposite?

While tackling

with any question pertaining to Hinduism, N.K. Bose’s work “The structure of

Hindu Society” becomes very important. As Bose turns out to be 1st

anthropologist who attempted to present organised principles of Hindu society.

By his knowledge on Vaishnava literature in Bengali and his familiarity with

distribution of temples, he has shown that ‘tribal’ and ‘non-tribal’ groups

have lived in mutual awareness of each other. Also, he points to the fact that

Indian languages have never made clear division between the term ‘tribe’ and

‘caste’ and the same term ‘jati’ in Bengali is seen to be used for both.

These fundamental aspects becomes very important while studying any dimension,

whether society, economy or religion as these shows that though tribal culture

often associated with local, marginalised or often termed as ‘low cultures’

based on the degree of their isolation may not have been that isolated as

thought to be and it is very natural that they evolved with contributing, or

adopting in and out with the so called ‘great culture’.

According to Bose

in India the two mode of social organisation, which may be loosely described as

the ‘Brahmanical’ and the ‘tribal’ have coexisted for a long time.[1]The Brahmanical mode always

attracted the other due to its superior technological base and the adaptative

ability of it which led the tribal to become part without abandoning their

customs. Many revivalist movements like the ‘Sanskritization’ brought these tribes

in mere consanguity with the wider and the superior Brahamanical social

organisation. His study on the Juangs or Savaras and Mundas and Oraons reflect

upon these arguments as these tribes are seen clearly to practise both the

‘Sanskritic’ and ‘non-Sanskritic’ elements. Bose has mostly given economic

reasons for such accultarations. For him stability and change to the social

life almost totally depend on the economic factors. This aspect he fused with

tribal life to show their adaptation to non-tribal one’s. For example, he

argues that the inability of shifting agriculture to provide desired needs

resulting in an increase on the burden of land led to tribes being adjusted to

advanced economic methods of the non-tribes.

Bose also proves

his argument by looking upon the technique of oil pressing in serakela

district. He felt that the tribal people were under constant pressure to

abandon their isolation in favour of absorption into the wider society, and

this pressure was mainly generated by economic circumstances.[2]He argues that when

external pressure led the stucking of tribal economy due to their technological

backwardness, they got absorbed to Hindu civilisation.

If we look upon the Tribal religious practices,

we do see many practices which can be associated beneath the Hindu Brahamanical

culture while there are some who are autonomous, which still bear intrinsic

tribal character. For example, the Juang tribe of Orissa, who leave in the

upper areas of Mahanadi has many features like the bath, the fast, the incense,

the use of turmeric and sun dried rice, the invocation of names like

Lakshmidevata, Rishipatni- give evidence of Brahamanical culture.[3]However, some practices

like the cock sacrifice, the worship of Burambura, Buramburi etc do have

intrinsic Juang character. Though Bose has shown tribal culture to be primitive

which got absorbed within the Brahamanical social organisation. Many

anthropologists criticize this view claiming tribal culture to be rich,

positive, harmonious and autonomous. For example, K.S Singh in his work,

“Hinduism and Tribal Religion: An Anthropological Perspective” argues the other

way round claiming that both Hinduism and Christianity are in fact trying to

tribalise themselves.

K.S Singh goes on

saying that many elements of tribalism gets into the named great traditions

time o time and they cease to exist. So, there is high chance that those

elements will vanish from the present tribal culture and come to be associated

as being always the part of Great traditions which they are not. He claims that

many of the elements described as tribal or aboriginal, particularly the tantra

traditions had already been absorbed.[4]The process got completed

in early medieval period itself with tantra works being written down in

Sanskrit. Sir Alfred Lyall argue that Brahmanism is a proselytising religion

and it still does so in 2 modes: 1st being the gradual Brahmanising

of the aboriginal, non-aryan, or casteless tribes who pass into Brahmanism by

natural upward transition, leading them to adopt the religion of the castes.

The process like Sanskritization, Brahmanisation, counting in census data etc

all have led to large number tribals to being associated within the ambit of

Hinduism and Christianity during the 19th century.

Inspite of the

long years of interaction with the Hinduism, Christianity etc the tribal

religion has not lost its distinct identity. Many elements of tribal religion

are as alive and vibrant as ever.[5]However, there are many

evidences of relationship between the tribal religion and Hindu shrines. The

Soliga tribe of Mysore regard local Vaishnava diety Rangaswamy as their

brother-in-law. They also observe fast on Saturday. The Chenchus of Nallamalai

hills adopted Shaivism in middle ages making Shiva (Srisaila Mallikarjun) as their

brother-in-law. However, they later adopted Vaishnavism to make Narashimha as

their brother in law.

Another good

example is the worship of Jagannath cult in Hinduism. Jagannath is crafted in

wood and wood as a medium is widely used among the Mundari groups of tribal

people. Many Mundas associate Jagannath as their god Marang Buru. It was the

Savara community who discovered Jagannath as their Savara deity. Like Jagannath

there are examples of many dieties who are associated with myriad of tribal

cultures with having association with Brahmanical Hinduism. For example,

Danteshwari of Bastar who is apex tribal in the Bastar, she is also worshipped

as local deity Mauli at village level and she is also Kali and Mahadurga, twin

faces of Mahashakti.[6] Similarly Chamudeshwari of

Mysore sets upon another example.

G.D Sontheimer

also argues on this speciality of Indian culture taking Jagannath cult as the

best example for showing the unity of different aspects of Hinduism

concentrated in one cult and the nearly uninterrupted continuity from tribal

beliefs to the highest philosophy.[7] In iibidVana, the more the

tribal cults were integrated by an exceedingly slow, but steady process over

centuries.[8]Slowly they got transformed

and assimilated to cult and rituals of Kshetra. Thus, the natural element got associated

through the myths used by ritual experts. Though they got transformed their

association could be still study as there still exist some manifestation of

Brahmanical themes. For example, Brahma, himself the unmanifest brahman thought

to be creator of world in Hinduism is very mush associated with forest as we do

see that fish, tortoise and boar were forms of Brahma before they got linked to

Vishnu as his Dashavataras, another supreme god among the trinity. Even lord

Jagannath whose murti is made of wood by finding a holy wood again shows forest

and trees as a source of renewel.

Sontheimer also

points to an interesting fact that it was in the forest, away from the settled

society, where the Buddhist monk, the Brahmin: vanaprastha, the samnyasin, the

Saivite Gosavi, the Lingayat virakta could have those spiritual insights and

revelations which caused them to formulate principles of universal

applications. The dandakaranya or dandakavana is said to be the quintessence of

the world and the seed of dharma and the Mukti in the Brahmanapurana[9]. Also, Shiva with his

manifold manifestations can be seen as one of great integrators of vana and

kshetra.

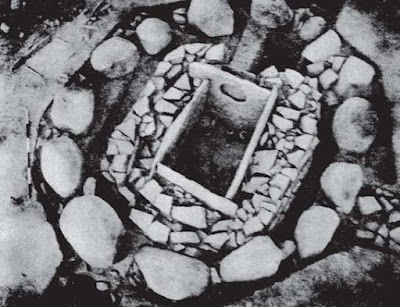

Symbols do play a

very important role in studying a societies economic, social, political and

religious aspects. In arena of religion symbols can open up those arenas for

study which hardly any aspect can do. Anncharlott Eschmann has thus highlighted

upon this aspect in her article, “Sign and Icon: Symbolism in the Indian Folk

Religion.” -In India, the tribes who used to live in large part of the country

even presently occupying much of area follow their own social order and

religion and hardly worship an icon and have almost no anthromorphic

representations of dieties which would be relevant to the cult. Practically

only elementary symbols or aniconic signs are relevant to the cult.[10]For example, trees, pots,

stones etc. Also, the divinity can be represented mostly by several signs

combined together to infer upon an imagery or more appropriately a symbolism of

the divine one. These signs are not icons as they do not indicate a form of a deity,

however, they do represent his presence, having a symbolic effect. These are

signs are used for performing the sacrifices. While these sacrifices are

performed, we do see that these signs represent the deities symbolically as

they are on the receiving end of it though it maybe to a lesser extent but we

do see a person, i.e. the shaman who communicate with the god, conveying the

divine presence inside him. Eschmann argues that but indeed the same function

is provided by the icons in later Hinduism-namely to mediate the real presence

of the divinity with which the devotee can communicate.[11]

Eschmann takes

the word Hinduization rather than Sanskritization for integration of tribal

religion in Hinduism as the later one is very much derogatory and is criticized

because of its limited use to language integration. She argues that the process

of Hinduization is basically affected in two directions. On the one hand, gods

of tribal religions, with their symbols and cults take up Hindu elements-names

of gods, rites, conceptions-and through this, ephemeral though this

assimilation may be, are “reputable” for Hinduism.[12]According to her this

takes place most in Hindu village, i.e.

in the folk religion. These are also called the “Little Tradition”. But

these little, regional tradition is also an independent component of the Great

Tradition which gradually gets integrated to it.

Moreover, the

signs are often seen to have become icons with time. For example, goddess

Stambhesvari, worshipped in Orissa, meaning the Lady of the Post is known to

have been worshipped in Hinduised forms since 8th century A.D. She

is also worshipped among the Khond tribe presently. Her sign is a post which is

a wood which is often replaced with time. To before the post is displayed in

Khond villages, a brahmin is brought who whispers the life-giving mantra to the

cut, giving life to it, thus making it somewhere symbolic to Hindu idol of god.

Further more rituals are accepted from Hindu icon worship. Also, somewhere a

stone is used as a post where both tribal settlement and Hindu village worship

it. This ambivalence between sign and icon, which is typical of folk religion,

continues all the time.

The process of

religious integration makes one of the important aspects of integrative Indian

culture. It is almost impossible to explain Indian culture, keeping its

diversity per say, to be of isolationist one, every aspect of it has been a

resultant outcome of dynamic process of integration, same with Hinduism.

B. D. Chattopadhyaya argued that

though goddess-worshipping is an archaic tradition, from the 4th-5th

centuries onwards, goddesses began to be a part of the Brahmanical culture.

We find many more goddesses such as

Aranyavasini, Ghattavasini, Vatayaksini from the copper plates. The

inscriptional data provided by Dr. Chattopadhyaya shows one common point that

these inscriptions were issued by a ruler or are related to a ruler in some way

or the other. Therefore, it seems that local rulers tried to patronage local

deities to seek legitimization and to strengthen their sway over their domain.

This process of integration of local

deities into Hinduism is termed by him as ‘Brahmanical mode of cult appropriation’.[13]

Conclusion

Hinduism can be

studied only through myriad facets, broadly terming itself as religion is a

failure in its understanding. It is even more than the cultural aspects. Thus,

driving present study on it mostly concerned with its organisational and

institutional aspect. Tribal religion is not something which maybe separate but

instead are effect of regionalisation. They are the local forms of Hinduism

with their shamanistic practices, rituals and worship of local dieties. Though gradually

time to time they must have been added on with greater traditions. The Bhakti

movement, Sanskritization, Brahmanization, the accounting of census has caused

their fast fusion with the greater culture giving a complex picture. Hinduism

has acquired a character of a way of living, limiting to a religion is ignoring

its multiple character.

Bibliography

2) Chakrabarti,

Kunal. “Cultural Interaction and Religious Process.” In Religious Process: The Puranas and Making of a Religious Tradition, by

Kunal Chakrabarti, 81-108. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001.

3) Chattopadhyaya, Brajadulal. “Reappearance of the Goddess or

the Brahmanical Mode of Appropriation: Some Early Epigraphic Evidence bearing

on Goddess Cults.” In Studying Early

India: Archaeology, Texts and Historical Issues, 172-190. New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2003.

4) Sontheimer, Guenther-Dietz. “The Vana and the Ksetra: The

Tribal Background of Some Famous Cults.” In Religion and Society in Eastern India, edited by G. C. Tripathi and

Hermann Kulke, 117-164. Bhubaneshwar: The Eschmann Memorial Fund, 1994.

5) Eschmann, Anncharlott. “Sign and Icon: Symbolism in the

Indian Folk Religion.” In Religion

and Society in Eastern India, edited by G. C. Tripathi and Hermann Kulke,

211-233. Bhubaneshwar: The Eschmann Memorial Fund, 1994.

[1] Bose, N.K. The

Structure of Hindu Society (Translated from Bengali by Andre Beteille). New Delhi: Orient Longman Limited,

1975.p-5

[2] Ibid.,

p-19

[3] Ibid.,

P-34

[4] Singh,

K.S. “Hinduism and Tribal Religion: An Anthropological Perspective.” Man In India Vol. 73, No. 1 (1993):

1-16., p-3

[5] Ibid.,

p-6

[6] Ibid.,

p-9

[7] Sontheimer,

Guenther-Dietz. “The Vana and the Ksetra: The Tribal Background of Some

Famous Cults.”, p-118

[8]

Ibid., p-129

[9]

Ibid, p-146

[10]Eschmann,

Anncharlott. “Sign and Icon: Symbolism in the Indian Folk Religion.”, p-214

[11]

Ibid., p-216.

[12]

Ibid., p-217

[13] Chattopadhyaya,

Brajadulal. “Reappearance of the Goddess or the Brahmanical Mode of

Appropriation: Some Early Epigraphic Evidence bearing on Goddess Cults.” In Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts and

Historical Issues, pp. 175-183

Comments

Post a Comment