How significant was craft production in the political economy of Vijayanagara, the imperial capital city between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries CE?

Introduction:

The Vijayanagara is seen to have ruled by four dynasties the Sangama (c. AD 1350–1486), Saluva (c. AD 1486–1505), Tuluva (c. AD 1505–1569), and Aravidu(c. 1569–1654) dynasties. The period of Vijayanagara Empire is seen to be a period of dramatic change in South Indian society and Economy with the marked appearance of new political and military structures, increase in urban centres, increase in monetization, expansion in craft and agricultural production, population growth from the earlier periods. Though the evidence of material production and consumption can tell archaeologists a lot about organisation of production and social, economic and political status of a society, it can be also seen that the vis-a-versa is also true and with the most possible assumption that the increase in political complexity will lead to increase in craft production in state societies. Though it is evidenced that craft production was proliferating during the period of Vijayanagara, how far it was important for its growth of political economy remains a question to probe.

Vijayanagara State:

Historical and Geographical background:

The States before the emergence of Vijayanagara in South India like the Cholas and the Chalukyas of Kalyani, Hoysalas and Kakatiyas are seen to have increasing political and social complexity as well as agrarian and demographic expansion in dry upland areas. As argued by Hitzman, the Chola state showed the temporal and regional variability with numerous centers of power including the ruling dynasty, regional elites, the temples, merchants guilds, artisans etc.

The Vijayanagara state like the preceding states emerged in South India’s inland semiarid uplands, a harsh area with unpredictable rainfall that poses considerable challenges to agrarian expansion(ibid. : 82). Hence, the territories were discontinuous and depended on how agriculture was expanded to forested regions. The Vijayanagara Empire which emerged in 1350 C.E with Sangama brothers occupying the areas near Tungabhadra river, the semi-arid uplands of central Karnataka and expanded to present day Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu. The western regions are mostly rugged hills, but the eastern areas have pockets of arable soils which can be productive with the irrigation. The region is seen to be arid but with reservoir construction, it is seen to be developed as agriculturally productive, with upland areas are seen to be as a major center of textile production because of good cotton productivity and also iron ore producing area. The eastern areas of Tamil Nadu are seen to possess the fertile deltaic region which had dense agricultural settlement and multiple urban centers and temple towns characterized this region even prior to Vijayanagara and during the Vijayanagara even areas of low productivity is seen be made productive by construction of reservoirs and canals.

Historiography:

The State in precolonial India (1000-1700A.D) is defined by different scholars differently, with basically five models as provided by Herman Kulke, the Asiatic Mode of Production and the Marxist model of Oriental Despotism, the Indian historiographical model, feudalistic, segmentary and patrimonial State. The earlier writings focused Asia to be a despotic state, with Adam smith arguing that the State derived its wealth from tax or rent on land, rather than from commerce and manufacture(Ibid :44) thus not promoting free market economy. The Indian historiographical proponents have only seen this despotism in a positive way and have argued for the existence of a strong and centralised state.

The proponents of Feudalism claim for the disappearance of powerful States, urbanism, and long-distance exchange, and the expectation of an isolated and dependent peasantry, all imply a decline in the role and power of merchants and artisans and an overall decrease in production(ibid. : 54). Karashima has argued for feudal state in later part of the Empire by focusing upon the economy and craft production of the period.

Based on the segmentary state model of Aidan Southall, Burton Stein argued that Vijayanagara was a polity of chiefdoms, with local social segments. He argues that Vijayanagara lies somewhere in between of segmentary and patrimonial state with in later stages progressing to centralized state. The foci of Vijayanagara political and economic segments is seen to be military leaders, who were ceded territories in exchange for service to the crown, and coastal chiefs, who benefited from expanded long-distance trade, particularly in textiles (ibid. : 57).

Nature of state:

In the Vijayanagara Empire, power, political and otherwise, was distributed among imperial and regional hereditary elites and administrators, military officers, temple institutions and leaders of diverse religious sects, merchant associations, and various caste and regional organization (Sinopoly, 2003 : 3). As we see that with the expansion of Empire during later Sangama rulers there is evidence of appointment of Governors, the rajyas or uchavadis. There is also evidence of Brahman officials and construction military fortresses since the time of Devaraya II. These local administrators were responsible for collecting the revenue. The peasant uprising documented in varied inscriptions of the period reflect the oppressive rates of taxation by these local administrators. There is also evidence of emergence of Telugu warriors, the “Nayakas,” in the southeastern regions with the expansion of Empire under Saluva and Tuluva dynasty. Though the class of Nayakas was created by Vijayanagara they are seen to be gaining autonomy with time as argued by Stein and Karashima. Even in the upland core areas we have evidence of local Kannada elites, the “poligars,” ruling small territories and providing forces to Vijayanagara empire. Thus, it shows that there were numerous centres of power which must have conflicting interest promoting economy in diverse ways with numerous patrons for craft production creating also changing political and economic structures, also, according to Sinopoly, this must have created much social mobility among crafters.

Temples are seen to be major institutions in Vijayanagara by being centres of considerable wealth and power becoming an important center for economic and urban expansion. As Vijayanagara kings were Hindus, the Shaivites and Vaishnavites hence they donated largely to it. It is reflected by the titles used by them like the “protectors of the deities of the Hindu Kings,” and “establishers of the Vedic path,”(ibid. : 93) etc. The records of grants inscribed on the temple walls must have become as a symbol of showing power among the elites increasing political competition between them. Since, the large pilgrimage centers of South India, such as Tirupati, Tiruvannamalai, Kanchipuram, and Srirangam, among others, underwent dramatic growth during the Vijayanagara period, it shows temples became centres of urban expansion which in turn must have led to economic expansion as these towns also emerged as commercial centres which in turn must have led to increasing craft production due to the increasing demand. In fact, the temples must have been major consumers of craft goods like garments, jewelry, precious stones, also there must have been need of musicians, sculptors etc increasing their production.

However, the peoples are seen to be worshiping numerous deities , local gods etc with even following Jaina and Muslim saints evidenced from the existence of large number of shrines and temples also reflecting the large number of craft producers must have been there for providing materials for them.

Craft Production and its Significance:

Considering Sinopoly’s broad definition to craft, i.e goods having both tangible and intangible outcomes requiring some skilled knowledge for production, thus including crafters like the potter, weavers, metal workers, stone cutters etc. and also bards, poets, musicians etc. It can be seen the Vijayanagara encompassed varied craft production. Both elite and non-elite craft goods are existent during the period. As we have textiles of both fine cotton and silk and coarse cotton clothes. Iron smiths producing both weapons and ploughs etc. Hence, we do know their must have been patrons for elite goods but we do not know if the producers only produced for them i.e if they controlled their production as production could also have been market centric.

It can be seen that the craft products were highly specialized during the Vijayanagara period only to have increased later. As, we do know that there were numerous centres of power, obviously the social competition between them must have increased the demand of craft goods. Also, the writing of Eaton and Wagoner has shown the connections of Vijayanagara with Bahmani sultanate emphasising the inter-polity movement of artisans which could have been there which is also evidenced from the similarities in architecture of both States, clearly this must have increased the number of patrons for these artisans.

In the case of poetry and literary works, we can see some direct influence by patrons for greater specialisation like in case of court poets facing their critiques and praisers. Also, we do see poetry writing flourishing in non-courtly sphere like the temples poets, for example Dhrujati and wandering bards etc. The high degree of specialisation in the case of music and dance are also evidenced from the sources like temple inscriptions, texts and sculptures depicting such performances. Like the poets the dancers were also important symbol of royal status and hence gaining their patronage. Also, the role of temples in patronizing them could be immense with the existence of male and female performers like the Devadasi. The example of inscription of Hanumasani making a cash donation of 820 nar-panam shows the enormous wealth the dancers could have gained but also showing the non possession of choice and place of labour associated with such artisans.

South Indian textile production is another area where high degree of specialisation can be studied. The high degree of specialisation needed for weaving the fine yarns of the cloths and their symbolic representation for showing the wealth in society led to their increasing production to serve the demands of expanding elites in the Vijayanagara. Even south Indian textiles were highly valued in Europe and throughout Asia(ibid. : 172). Also numerous caste of weavers like the famous kaikkolar community along with the Devanga, Sale, Jade etc show the high degree of specialization, also the gain they were making can be reflected by roles they played in temple administration and activities.

It can be seen that due to existing high degree of specialisation, the producers were interconnected in various ways with different artisans, state, and other institutions like merchant organizations, caste organizations, individual producers etc. For example, if we take the case of iron and steel production which was in high demand in international commerce at least at the end of Vijayanagara, we do see that apart from the large-scale producing source areas of inland Andhra Pradesh and western Karnataka, blacksmiths and smaller-scale smelting were widespread in rural and urban contexts throughout South India – producing and repairing cart wheels and agricultural tools, and manufacturing swords, arrow points, guns, armor, and other military hardware(ibid. : 193). Along with specialists like miners and charcoal producers it also requires wage labourers for work like mining. Also, iron smelting requires furnaces and tools for forging which also requires different sets of artisans.

During the time of Vijayanagara, we do see sacred and secular administrative institutions were closely and complexly interconnected. Local and imperial administrators often reallocated tax and other revenues to temples and communities of Brahmans, and also had the rights to grant temple and ritual privileges in some contexts(ibid. : 253). There are evidences of taxation imposed and revenue taken from the crafters by State and numerous institutions showing it was important for revenue generation but there is no evidence of direct regulations of such goods by these institutions.

Also, it is unclear about how much of the revenues collected were transferred to imperial centers, Karashima estimated it to on average around 30 percent. Even Stein has estimated it to be low.Taxes were collected on corporate units, tools of production, on their movement and also on finished products. Also, since the taxes were mostly collected in cash, it must have increased the interactions more in economy. According, to Karashima based on evidence from temple inscriptions by 16th century there is marked decline of taxation by royalty and imperial authority giving prominence to Nayakas.

The vijayanagara period show lack of proper synchronisation between the craft producers and patrons or consumers. As we do have evidence of protest against excessive taxation to the extent of mass migrations of such artisans. Also many inscriptions do reveal tax remission and reallocation with the latter being more prominent.

If we see the inter-relations between the State and craft production, no doubt the State did have a role to play but to what extent is a thing to probe upon. The imperial court were no doubt the largest consumers of luxury craft goods. Encouraging skilled and spatial distribution of craft goods. The changing fashion style also plays a role in encouraging new producers and new products. Also, the courts also get involved in other activities like building and court performance increasing the demand. Also, craft producers are also seen to be gaining patronage to create a class to pay taxes for maintaining the military, polity etc of the empire.

As far as role of temples is concerned it is seen to be immense as craft producers are linked to them in manifold ways.Some craft producers did provide their and in exchange they even got some privileges like land and in some cases they also acted as donors to them. An important feature to be noted is that there are also numerous small temples and shrines. The artisans who produced them travelled in small numbers compensated by individuals or communities which sponsored them.

We also have the non-elite consumer and craft producers relations to which influence the craft production though less documented.Such interactions were no doubt widespread and embedded in kin, caste, locality etc. They could have included, for example, a potter who provided earthenware vessels to a carpenter in return for wooden tools needed for ceramic production, or gave pots to a mason in exchange for stone anvils or building materials(Ibid. : 283).

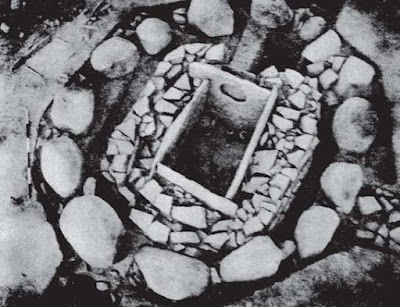

An important feature of Vijayanagara Empire is that despite the complexity of craft production which was existing we see lack of large scale, centrally administered units of craft production such as factories and imperial workshops(ibid. : 6). Most of the craft productions is seen to be taking place in small-scale household workshops.For example, the archaeological pattern of iron working in the Vijayanagara metropolitan region provides evidence for small-scale producers who moved across the landscape seasonally to serve a variety of consumers. Also in case of bronze working though we do not have any evidence of workshop we do see large number of bronze artifacts but with much lesser artistic quality then earlier works, even the majority of images are not signed or dated indicating localized production. Also, the evidence of stone quarry by Buchanan reflect that both cutting of stones from the quarry and shaping them to forms was done by same persons indicating unspecialized way of doing a work which in uncommon in factory production.

Conclusion:

As we have seen the study of nature of state and seeing their relation with craft production, obviously we know that there were numerous patrons for craft production resulting in their increasing specialization but as far as the role of State in regulating it is considered is seen to be very less with production mostly done on localized scale, also State is seen to be gaining very less amount of taxes from these production showing that political economy of the Vijayanagara was not indirect contributor to craft production but also indirect and minimal beneficiary of it. Thus, it can be seen though craft production was proliferating it had less influence on the political economy of Vijayanagara Empire.

Bibliography: 1. Sinopoli C M, 2003, The Political Economy of Craft Production: Crafting Empire in South India c.1350 – 1650, Cambridge: University Press

Comments

Post a Comment