In what ways were the pre-Indus (5000-2600 BCE) and post Indus (1900-1200 BCE) periods different from the Indus period (2600-1900 BCE)?

|

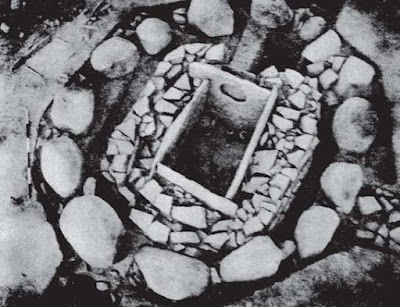

| source:https://indusvalley-harappa.weebly.com/uploads/3/9/0/6/39066825/header_images/1410361819.jpg |

The Indus period (2600-1900 BCE) often referred to as the Harappan civilization is amongst the oldest civilization known today, the other being the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilization. The absence of its mention in the literary accounts and the non-decipherment of its script has left us with archaeology as the only field to give some proven insights on the period. But with archaeology with its own limitations pertaining to excavation and differences on interpretation of artefacts provide us with only limited knowledge leading to no concrete notion about the period. Thus, it becomes a challenge to compare and demarcate it with surrounding ancient cultures with no uniform notion which can be decided upon.

The enlightenment years and the start of colonialism in

India prepared a ground for a spirit of inquiry about India’s past leading to

exploration works in the early 19th century. The earliest

exploration in the context of Harappa were done by Alexander Cunningham, who in

1850s, visited the ruins of Indus city of Harappa (Mcintosh, 2008) but no

perception about such an old civilization could have been made due to his focus

on Buddhist monuments and Early Historic cities. It was in 1920s during the

Marshall era that excavations of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro gave idea of Indus

civilization. As explorations and excavations of various archaeological teams

progressed thereafter, scholars used the term ‘Indus’ or ‘Harappan’

civilization, but increasingly became aware that its spread and the spread of

cultures that provided prelude to the civilization, was exceptionally wide,

beyond the Indus plains themselves. (Ratnagar, 2016)

As per wideness of Indus valley civilization is concerned,

looking upon it both temporarily and spatially, there is no clear consensus

among the scholars between the congruency and differences among the regional

cultures which appears to be existent simultaneously or pre or post to the

mature Indus period. In the late 20th century there was some

consensus among scholars where cultures like kot diji, sothi-siswal, amri,

cemetery H etc, pertaining to there differences in local techniques, ceramics,

house forms etc, were proved to be different then mature Indus period. There is

some clear continuity at many sites and within their material culture but no

evidence for a seamless, smooth transition (coningham and Young, 2015) is there

between these periods.

The Indus civilization or the mature Indus period is

differentiated from others on basis of great standardisation, uniformity and

development which prevailed in it as compared to others. But while saying it as

a civilization or developed period, the question which can be raised is what do

we even understand from these words? Presently,

most of the archaeologist see it from the eyes of development in material

culture and this becomes the criteria for differentiating it with other

surrounding cultures which declined or emerged after it. Possehl even argue on

the basis of greater rate for the founding of Indus new settlements from the

other stages of the Indus Age as a nihilistic behaviour referring it to a new

order of life.

Urbanization and sociocultural complexity are interrelated

and defining features of the Indus Civilization. The size and complexity of the

Indus cities are distinctive features of the Mature Harappan, not clearly

developed out of even the largest of the Early Harappan places. Water management

is also considered a distinctive feature. The many wells, elaborate drainage

systems, bathing facilities in virtually all of the houses, and the Great Bath Show

its importance. One of the most interesting features of the Indus Civilization

is the range of new technologies associated with it. This is best

exemplified in their metal work and the development of bronze. But it is also

apparent in the advancements they made with faience and stoneware, clear steps

upward on the pyro technological ladder (Possehl, 2002). Urban drainage

systems, manufacture of very long, hard stone beads, including the

sophisticated drilling technology, City planning and the

construction of large buildings from baked bricks etc are some features which

distinctly characterise the mature Indus period from the others.

The pre-Indus often now referred as the era of

regionalisation, the term firstly used by Shaffer in the sense for emphasising

period of an emergent urbanism and regional traditions. The developments in the

Indo -Iranian region since the emergence of domestication of plants around 7000

BCE to mature Indus period was considered as a separate development stage from

mature Indus but now this interpretation is challenged and the period is considered

to be one of dynamic experimentation, which developed in a shared cultural

complex circa 2800 BCE just prior to the emergence of Integrated Era of the

Indus civilization (Coningham and Young, 2015). The pre-Indus settlements are referred

to as “emerging politics” by Rita Wright on account of three factors. Firstly,

as they are coexisting political units in which no single group dominate any of

other. Secondly, there is evidence for active exchange networks. Thirdly, the

villages and towns developed during these periods are increasingly complex both

economically and socially (Wright, 2010).

As far as pre-Indus period is concerned there are many

phases which are looked upon depending upon differences in their chronology, ceramic

culture and geographical location. No doubt the study of these show an emerging

society which continued to form into mature one in the mature Indus period

however there are still large-scale differences. If the area of Baluchistan is

concerned, there are basically four phases, the Kili Gul Muhammad, Kechi Beg,

Damb Sadat and Nal Phases dating roughly from c.4300 BCE to c.2500 BCE. The

lower Indus mainly having the Balakot Phase (c.4000-3500 BCE) and Amri Phase

(c.3600-3000 BCE) while the Ravi phase (c.3500-2700 BCE) and Kot Diji are found

near area of Punjab and Upper Indus.

It is argued that the period had some specialisation as for

example from Kili Gul Muhammad Phase we have evidence of two type of mud-brick

structures, compartmental units measuring an average of 20 by 15 metres and

residential units. The compartmental units understood as granaries silos by

many indicating surplus production but the point is that size of these

structures is still not so big and the residential units are constructed by

clay and gravel and not bricks. Another interesting structure is a monumental

mud-brick platform almost 40 metres in length from Mehrgarh in Damb Sadat

phase. However, the actual height remains in question as the building is

collapsed however it can be thought to be some major importance. The Ravi phase

represents the earliest pre-urban occupation at Harappa here the structures

were built of wooden post and mud- brick structure is lacking (Wright, 2010). From

the Kot Diji there is evidence of massive mud brick perimeter walls and

platforms with uniform bricks (1:2:4) becoming principle building material.

According to Rita wright, this suggest fairly large scale community efforts,

shared system of measurement and presence of masonry specialists (Wright, 2010)

Kenoyer has argued that it may represent some form of early Harappan social

organisation capable of mobilising and controlling the production of large

quantities of bricks as well as the labour involved in wall construction

(Kenoyer 1991a, Coningham and Young, 2015).

Another aspect pointed out is presence of economic

specialisation. It is argued that beads and wheel turned pottery in pre-Indus

period must have required semi-industries. As for example from the Kili Gul

Muhammad phase we have evidence of a stand of ceramic kilns with circumferences

of 2.5 metres surrounded by a staggering six metres depth of ceramic wasters

also there is find of crucibles for smelting. Also, it is argued that since

most pottery containing some marks maybe identification of the workshop.

However, a major limitation of this argument is that the potteries are still

mostly unfired.

There is also the argument about long distance trade as there

is presence of lapis, carnelian and marine shells as trade can never be done in

isolation there must be exchange of information with other cultures. There is

also evidence of seal from Rehman Dheri with implications for recording and

trade however the scorpion engraved seals found from the site is totally

missing from mature Indus marks limitation to continuity of culture.

There is argument about presence of planned outline during

the period. B.B Lal’s excavation of Kalibangan has shown the remains of drains

constructed of backed bricks for water proofing. Another interesting aspect is

evidence of water channels following parallel lines resembling old lines of

street alignments is exposed from the site of Rehman Dheri by A.H. Dani. Durrani’s excavations also demonstrated that

the mud-brick and clay block walls of the earliest residential occupation of

the site respected the parallel orientation of the town walls, further

supporting the argument (Coningham and Young, 2015).

As far as evidence of writing is concerned, there is little

if any evidence for the beginnings of writing in the Early Harappan. Signs on

pots, both pre- and post-firing, begin early, in Stage Two, but this is not

writing, and some of it is probably simple potter’s marks or marks of ownership

(Possehl, 2002).

The post-Indus period is argued to have shown radical

changes from the mature Indus period. There is loss of traits associated with

the urban-focused settlements. But the transformation was not uniform instead

there was different transformation occurring in different regions (Coningham

and Young, 2015). It is seen that the towns were largely abandoned during this

period. Rao has noted that inhabitants of Rangpur phase started living in

jerry-built houses with reed-walls in contrast with the spacious brick-paved

dwellings of earlier years. (ibid) Though there is still evidence of manufacture

of tools they were mainly done with local materials. There is evidence of

crumbling urbanism as for example during the later stages in Dholavira, the

city is reduced surrounding the citadel. Also as argued by Bisht there was

progressive impoverishment as though some ceramic forms were still there it was

mostly replaced by Jhukar style ceramic and seals.

An interesting aspect about the period is that it is seen

that multi-cropping intensified during this period. Though there is measurable

decline in density of seeds being recovered it is founded by Weber that in the

post-Indus period a wider range of crops are grown by farmers then the

preceding periods. He has also shown that there was a shift in the sense that

the dominant crop emerged to be foxtail millet then the earlier finger millet

and little millet.

The post-Indus also show a major change in the relationship

with the dead as evidenced from the cemetery H phase there is abandonment of

individual burial and adoption of new practices is seen. Cemetery H is seen to

be divided into two phases, the first of which consisted of both extended and

fractional burial, including animal remains and artefacts and other phase with

fractional burials of more than one individual with no grave goods. The burials

show stylised ware as compared to plain ceramics of mature-Indus period

burials.

The Jhukar culture emerging in the late Indus period is

often considered degenerated version of mature-Indus period. Wheeler has also

argued that it represented “squatter-cultures of low grade” (Coningham and

Young, 2015). The culture is seen to be result of reoccupation of area which

was earlier abandoned. There is evidence of circular steatite seals from here

very different from the earlier period. Also, the pottery designs and shapes

are different.

As far as question of differentiation between the periods is

concerned, no doubt some continuity can be observed since the pre-Indus to

post-Indus periods but as per period of Mature Indus is concerned it is termed

as a civilization signifying some degree of massive specialisation and

urbanisation which is clearly absent in the other two periods. But it becomes

very important while dealing with such argument is realisation of the fact that

notions which is interpreted by archaeologists today is based on understanding

of present culture, they might have signified some other meanings in earlier

context. Also, there is a limitation associated with periodisation of culture

as we know nothing might have suddenly emerged or had disappeared. Moreover,

the environmental settings in which these phases emerged must have shaped their

culture as climate is always changing and while looking upon degree of

development related to material culture it becomes important to realise these

aspects as terms like development or specialisation are often subjective. Thus,

it still remains a difficult aspect while comparing such periods.

REFERENCE: 1. Coningham R and R Young, 2015, The Archaeology

of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE-200 CE, New York: Cambridge

University Press.

2. Possehl, G L, 2002, The Indus Civilization: A

Contemporary Perspective, New Delhi: Vistar

3. Ratnagar, S, 2016, Harappan Archaeology: Early State

Perspectives, Delhi: Primus.

4. Wright, R P, 2010, The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy

and Society, Cambridge university press

Comments

Post a Comment